In this series we actively invite scholars from Leiden, Delft and Erasmus to engage with issues on governance, migration and diversity from their field of expertise. In this episode, we invited dr. Nadia Bouras, Assistant Professor and Historian at Leiden University to talk with us about the LDE Centre GMD, migration beyond the ethnic lens and her new Dutch book.

By Lhamo Meyer and Mark van Ostaijen

Why is a historical perspective important regarding migration issues?

“It is very important to discuss current issues from a historical perspective. I think in society we have some sort historical amnesia, we don’t know any more what happened in the past. We think that everything what happens today is new, novel, exciting, pressing. Especially with issues as migration it is important to show that what we are experiencing in everyday life is not new or different from the past. A historical perspective gives us context, a comparative idea and an understanding of events that are repetitive. This is very important to counter this amnesia.”

And what is your personal drive to study migration?

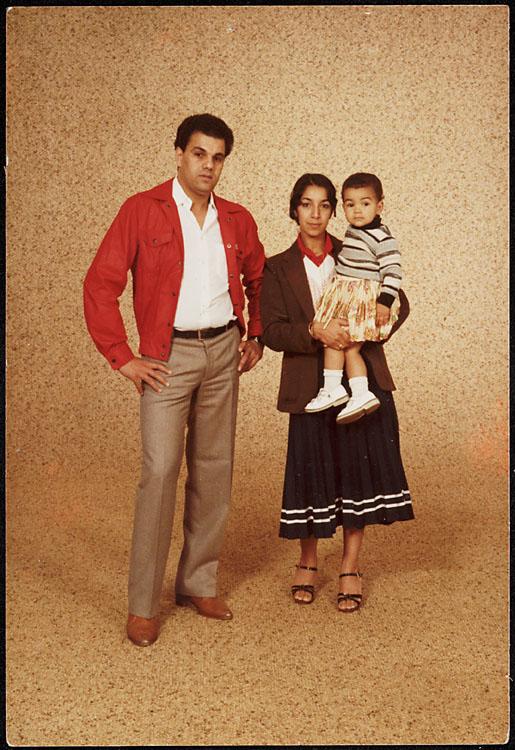

“I studied history at the Free University of Amsterdam and as every student I was struggling to find a topic for my thesis and then my supervisor, prof.dr. Willem Frijhoff, triggered me to do something with my Moroccan background. At the same time I visited an exhibition about the experiences of Moroccan women and got very interested in these stories which were similar to the stories of my mother. Whenever we talk about Moroccan migration we talk about men, guest workers, pensions, the horrible work conditions, but we never see the perspective of women. That was a gap in Moroccan migration history literature.

With my advantages of speaking the language, having a great network and being a child of migration, everything came together. Both my parents were migrants, I was born in Amsterdam and understood what migration is and what it means to stand in this long migration tradition. I got the opportunity to study my family history and therefore have a professional as well as personal interest in studying migration.

Migration is about vanishing and disappearing from society. This is why I consider it so important to keep history alive by creating ‘little monuments’ of and for my family and all the people who migrated back in the 60s. It is about making sure that those stories are known and the public engages with them so they become common knowledge. I am very happy and proud to have had this chance to write books on this particular migration history and feel privileged that I can do so.”

A historical perspective gives us context, a comparative idea and an understanding of events that are repetitive.

But do you think we should keep the ethnic lens on migrant issues or do you favour a more mainstreaming approach?

“I am not an immigrant myself, I am of the second generation Dutch-Moroccans, but I stand in this tradition of migration. I am a child of migration. Applying the ethnic lens is important as it is a fact. Ethnicity is not only tied with migration, as you can also be attached to your ethnic background when you are not an immigrant. It is about where you come from, the culture you belong to, the reproduction of that culture. I see that the second generation or children of immigrants are still strongly attached to their ethnic background but give different meanings to ethnicity. So we have to keep an open mind since ethnicity is not limited, rather it is one of the multiple markers of our identities. Moreover, identity is not only how you identify yourself, but also how society sees you. Intersectionality is important to employ all these different perspectives and make sure that we look at migration from a 2020-lens to answer questions which are important in today’s society.”

You are also affiliated to NIMAR, what is that and what is your role there?

“The Netherlands Institute Morocco (NIMAR) is the smallest institute of the Humanities faculty in Leiden located in Rabat. I am the NIMAR affiliate at Leiden University and give a couple of courses on Moroccan History and Moroccan Migration History, a collaboration between NIMAR and the History department. NIMAR offers History students in Leiden the opportunity to study in Rabat. You can always go to London, Paris, Berlin, so why not to Rabat? It is only three hours away by plane and you can indulge in a different culture in Northern Africa.

By adopting NIMAR, Leiden stands out being the only university in the Netherlands that offers the history of Morocco on a structural basis. Dutch-Moroccans are the second largest immigrant group and therefore it is important to consider this country’s history. Moreover, NIMAR tries to avoid an Eurocentric approach to migration by including literature from migration scholars outside of Europe.“

So don’t shy away being framed as activist. I see that as a badge of honour.

What are potential blind-spots for us as LDE Centre GMD and migration scholars in general we should be mindful about?

“In many university departments there is still a disconnect between the topics we study and how we integrate them in our everyday lives. This becomes visible with issues such as diversity which should not only be studied but also be engaged with when looking at the structures of our institutions. We have to be more proactive to make changes within our institutions.

The LDE Centre GMD was established in perfect timing and public discourse. There is now more support in politics and among the general public on topics such as migration and diversity. This provides you with the opportunity to be visible in current debates. So this centre has not only an academic purpose, but also a social purpose to inform the general public. As a centre you can be reactive but also proactive, which is even more important. We don’t need politics to tell us what to put on our agenda. Your centre can bring these agendas together, so peers know of each other’s work and can increasingly collaborate which strengthens a multi- and interdisciplinary approach.”

What is the biggest challenge in creating societal impact?

“As scholars we tend to be very nuanced but at the same time the public debate demands us to be different. We should stop being polite and lose ourselves in perhapses and maybes. We have a responsibility to inform the public with facts instead of myths. Our research is often informed by what is happening in society, so there is a spill-over from the public debate to academia and vice versa. So don’t shy away being framed as activist. I see that as a badge of honour. I think Twitter is a great platform to use and inform the public in different ways about research findings. Take yourself seriously, but at the same time be playful.”

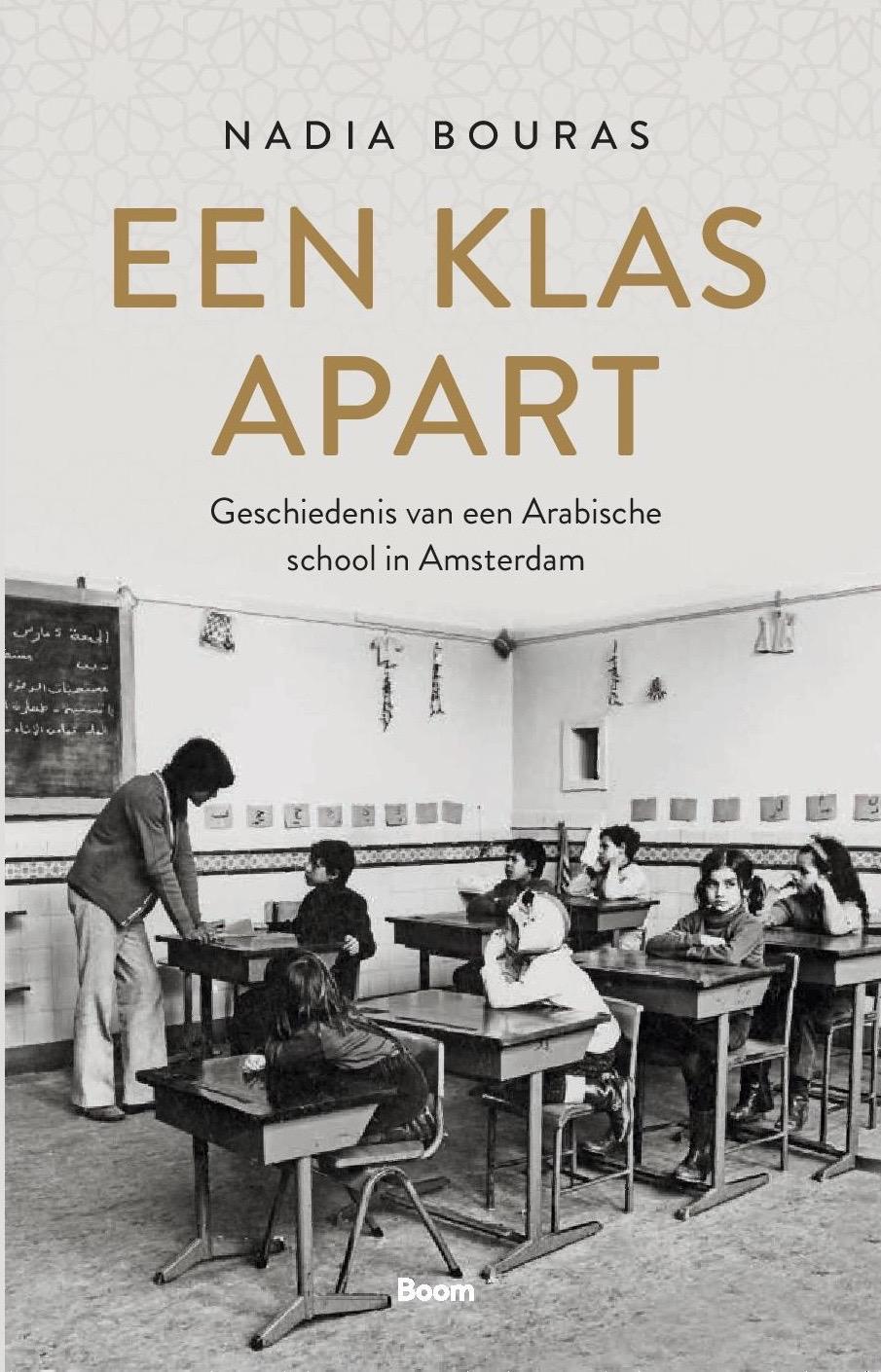

And finally, what is your new book about?

“My new Dutch book (Een klas apart, red.) is about my personal history and at the same time about the story of the school I went to and how it followed the trends of migration and contributed to a changing society. The book is about equality, education, personal histories and gives an overall picture of the multicultural society in a school in Amsterdam. It shows that you cannot escape from yourself and your multiple identities.“